On Sunday, I decided to give myself an hour at a museum before finishing a midterm and other classwork. After some consideration, I chose to head over to the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) and take in Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano. I know this will sound like a type of art history heresy, but I have never been a big fan of Whistler. I find his portraits to be slightly jarring and formulaic. However, I am a fan of Sargent’s looser brushwork and depictions of genre scenes that, despite being contrived, look as if he is capturing a fleeting moment. As for the glasswork inclusion, I am never against looking at glass objects, be they Venetian or not. However, I don’t yet know enough about the medium to make a critique that dives deeper than the shallowest of aesthetic judgment.

It is always interesting to see what other artists are included in exhibitions anchored on such well-known names from the canon, and this one was not disappointing. The Venetian Lacemakers by Robert Fredric Blum was well-positioned between two windows which played off its composition of women seated near windows taking advantage of the sun for their delicate work. The depiction of giddiness and having a gossipy nature turned them into a tronie that demoted them to objects. Still, the artist’s depiction of light and shadow was visually striking.

SAAM made a wise choice in placing a display case of lace from that time period crosswise to serve as a room divider. It also served as a link to the products that the highly skilled real-life laborers, alluded to in the painting, produced.

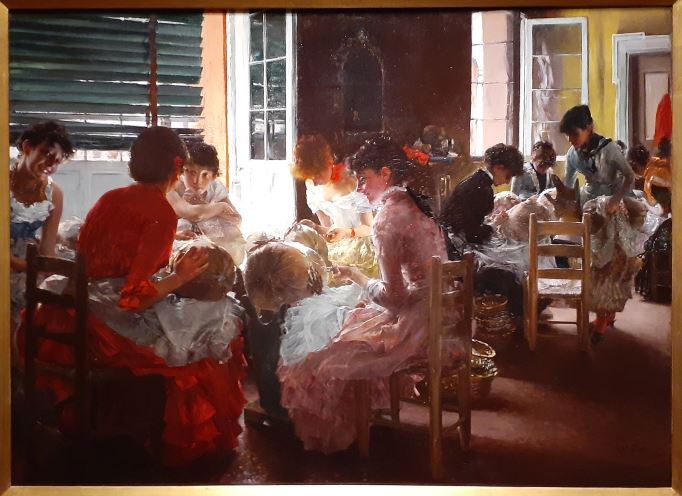

To the left of Blum’s work hung John Singer Sargent’s Venetian Glass Workers. The artwork is likely a staged scene inspired by direct observation. What I find most interesting about it is that he veers away from the trappings of the artistic canon’s historical past by not depicting the working class as a caricature of the happy downtrodden. Like in his street scenes, Sargent has avoided a composition that looks contrived. Unlike in Blum’s work, none of the models are the focus of the artist’s singular attention. There is no pretense to a narrative outside of the physical labor of bead-making.

I have a preference for portraits that are executed on a smaller scale. I find them more intimate and approachable. This led me to the small pastel portrait included in the exhibition by Frank Duneneck that is unfortunately titled Gypsy Boy. The boy looks not particularly interested in having his portrait done as he stares forward in a state of ennui with his hair disheveled just right. I found the composition rather lovely. Just enough spontaneity in the marks to give it an aura of a moment between moments. Finished just enough for us to know that the model sat for the artist but unfinished enough for us to imagine that the child bolted off to go do anything else as soon as he was allowed.

Circling back to the discomfort I have with the title’s use of the “G” word. The word Gypsy is problematic. Its origins are racist, however, in the United States, the context that it is being deployed in normally connotes if I should be egregiously offended or not. Since Romanies are not without any representation in the artistic canon I did try to withhold judgment and tried looking at it through a historical lens where at the time, appropriate or not, it was the commonly used descriptor. But I was not made to feel any better by reading the description that accompanies the work.

The pastel is in fact another time amongst many that my ethnic group was used to provide dramatic flair to an unrelated work of art. The portrait “is most likely a local Venetian (not Roma), and American viewers of this work might have associated him with frequent depictions of “Young Italy.” There is so much to unpack in those words. Certainly, more than I will do here. Instead of jumping down the hole into everything that is wrong with the othering and commodification of a Venetian boy or asking why they felt the need to use punctuation that segregated to word Roma from the rest of the sentence I am going to ask questions and provide one positive critique.

First, I want to know how they arrived at using the word Roma. I have a friend that is Roma. I am a Romanichal. We are both Romani. So I am interested in how they chose a world that is specific to a group of Romanies and not our over-lapping umbrella term.

Did they consult a Romani language specialist or a native speaker?

Did they look up what group was most likely to be in Italy at the time the boy was rendered by the artist?

Did they just do a bit of research and think they got it right?

Did they guess?

Now for the positive.

They pointed out that it was not a chavo. (Romani Boy) Not that long ago museums would not have bothered to mention such a thing. If anything they would have bitten off on the use of the ethnicity as narrative and expounded some romantic ideas about the boy and why the artist chose him. I know this because I remember reading those kinds of things. So credit where credit is due. A change for the better has happened. May it keep happening and improve.