“The success of a museum as a community center is measured by the cooperative spirit existing between the museum and its public.”

— Janet R McFarlane, Museums as Community Centers, 2015

Today’s speaker was the Anacostia Community Museum Director Melanie A. Adams, Ph.D. Other members of upper management spoke as well but I, unfortunately, did not catch all their names. It was notable that they all concentration on the museum’s mission of being community first despite carrying the weight that accompanies the Smithsonian brand. I learned that the museum was founded in 1967 at the behest of the sitting Secretary. He hoped to bring the Smithsonian to Anacostia in a propagandized manner to quash what he saw as sociopolitical threats stemming from the civil rights movement. Unfortunately for the Secretary, the museum’s first director John Conrad, a community organizer, had other plans.

Conrad’s vision was of a museum that reflected the surrounding community. The museum is still functioning as a community-centered institution, although it is seemingly having trouble defining its boundaries. I am only aware of this because a classmate and professor who are locals to the DC area both pointed out how far some of the restaurants shown in the exhibition Food for the People are from the museum. This expansion past the surrounding neighborhoods may reflect a shift in identity by the Anacostia Community Museum instigated by the National African American Museum of Culture and History opening its doors and taking over the role of telling the history of African American diaspora. Before this, the Anacostia Community Museum had fulfilled that social responsibility.

I believe that the exhibition is highly successful and impressively assembled. None of the museum’s small footprint was waisted, nor was it so overloaded that it became visually overbearing. Overall, I would say that this exhibition is aimed towards families with elementary-age or older children. In non-pandemic times it would serve as an excellent school trip for older elementary students and up through high school age.

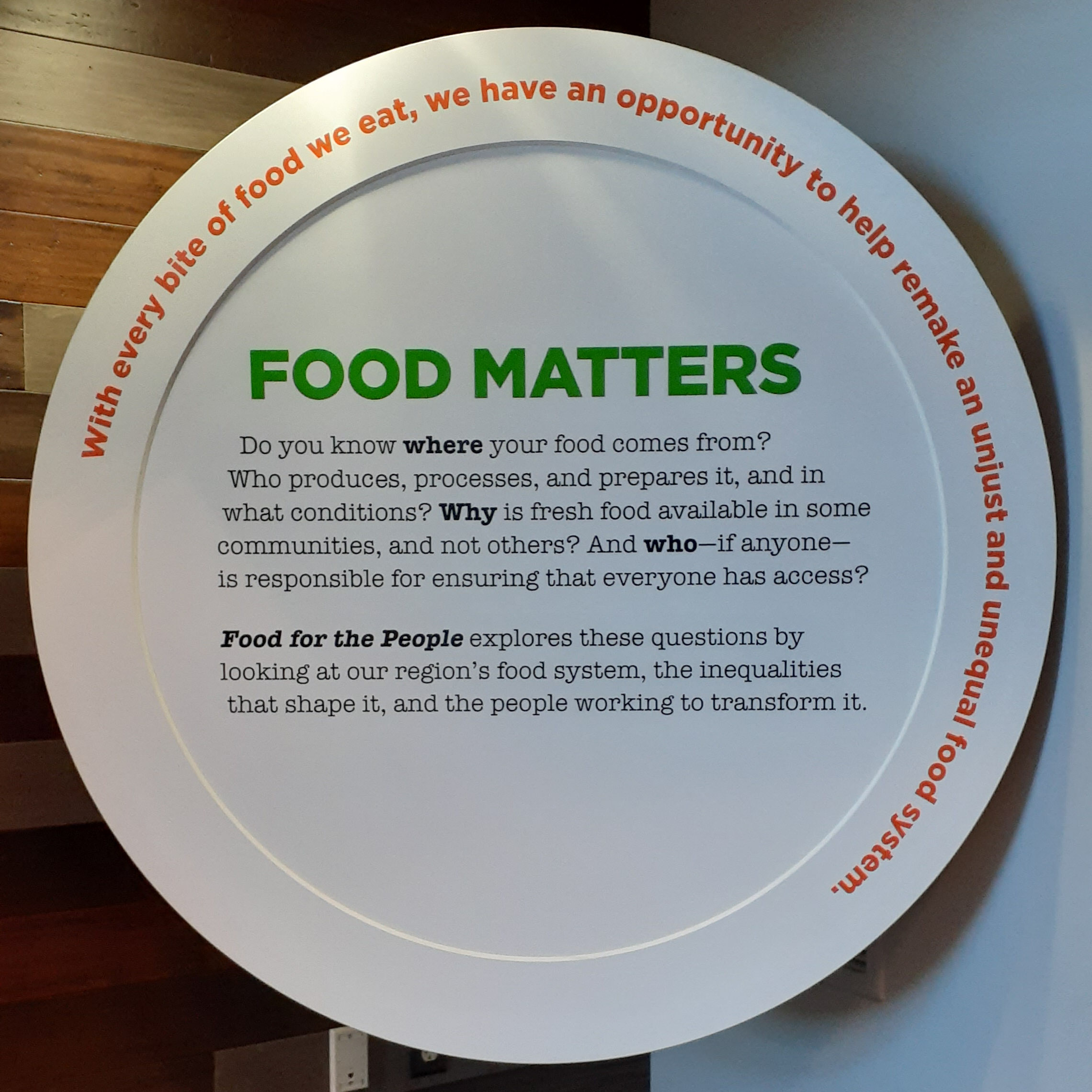

The museum’s front walkway is filled with displays that compare food production to issues of access. Visitors are whimsically confronted with literal pie charts referencing government spending on food programs when they walk through the front door.

It is deplorable that food is politicized, but it is an inescapable truth. This truth was shown throughout the Anacostia Community Museum’s Food for the People exhibition. The history of nutrition programs and their use to try and control the behavior of the African American population, particularly during the civil rights era, was displayed with chronological clarity. The exhibition addresses the inequality of access to food that residents of the surrounding neighborhood currently face and how this is a systemic problem historically affecting communities of color across the country.

Aesthetically speaking, the museum’s use of green and orange in the exhibition reminded me of the North Texas Food Bank distribution center. Upon further reflection, I realized that many other, for lack of a better term, “pro-food” organizations that I am familiar with also use that same color palette and font in their advertisements and public outreach programs. After returning to school, I accompanied two classmates to Subway and found similar colors deployed there. Is this a Subway effect, or is this derived from some other branding research that showed people respond better to a narrow color palette that includes green and orange when viewing food advertisements? Or is this just a case that out there somewhere, a graphic designer produced a highly attractive advertisement that has now been washed and repeated to the point of becoming the quasi-official branding colors for food-related ventures? If so, it makes perfect sense for nonprofits and museums alike to utilize it to attract an audience.

Images

Top Left: Anacostia Community Museum

Bottom Left: North Texas Food Bank

Right: Subway, Washington DC

An interactive harvesting exhibit timed your ability to pick tomatoes to see how much you would make if you worked in the commercial farming industry. This activity, while aimed at younger audiences, was attractive to my adult classmates. The timmer combined with a comparative pay chart was an effective tool to create empathy for the plight of migrant workers regarding the low pay they receive for their physically high labor. The exhibit was socially successful in creating a dialog between visitors. A classmate told me about his youth where he and his brother were paid ten cents a pound as blueberry pickers, and I replied with my experience picking pecans when I was a kid for a payout of five dollars a bag. Both of us worked these jobs for extra spending money, but our experiences differed in that he saw how it was a livelihood for others while working side by side with them due to the farmed nature of the work. Whereas I did not have that experience as there was no centralized orchard of pecan trees in my town, you just had to find trees that grew throughout the area that were free of infestation and readily dropping their nuts. I never bothered to learn how much the bags weighed as we just had to stuff enough high-quality pecans into them until you almost couldn’t get a twist tie onto the top for it to be considered full. I rarely saw adults out gathering nuts but regularly saw them at the turn-in building. So I was not unaware of the true laborers, just not as acutely as my classmate.

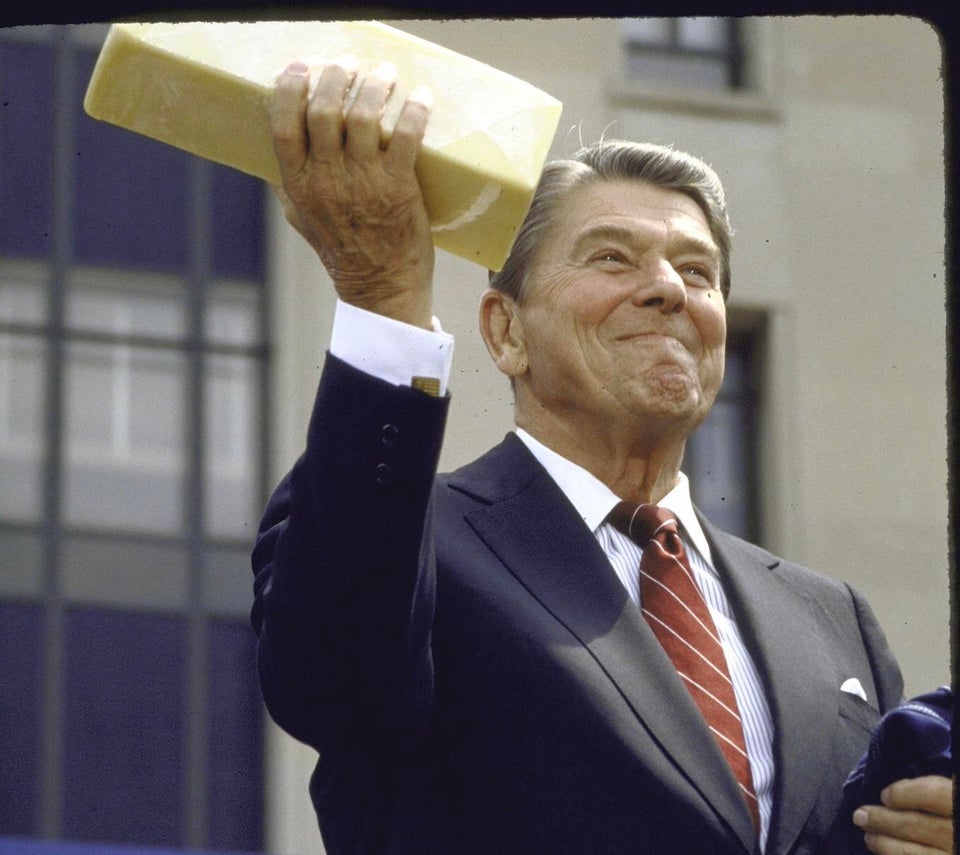

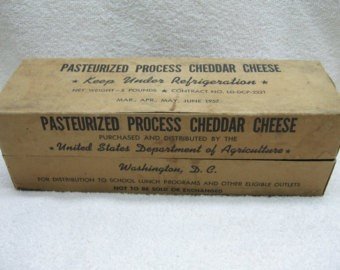

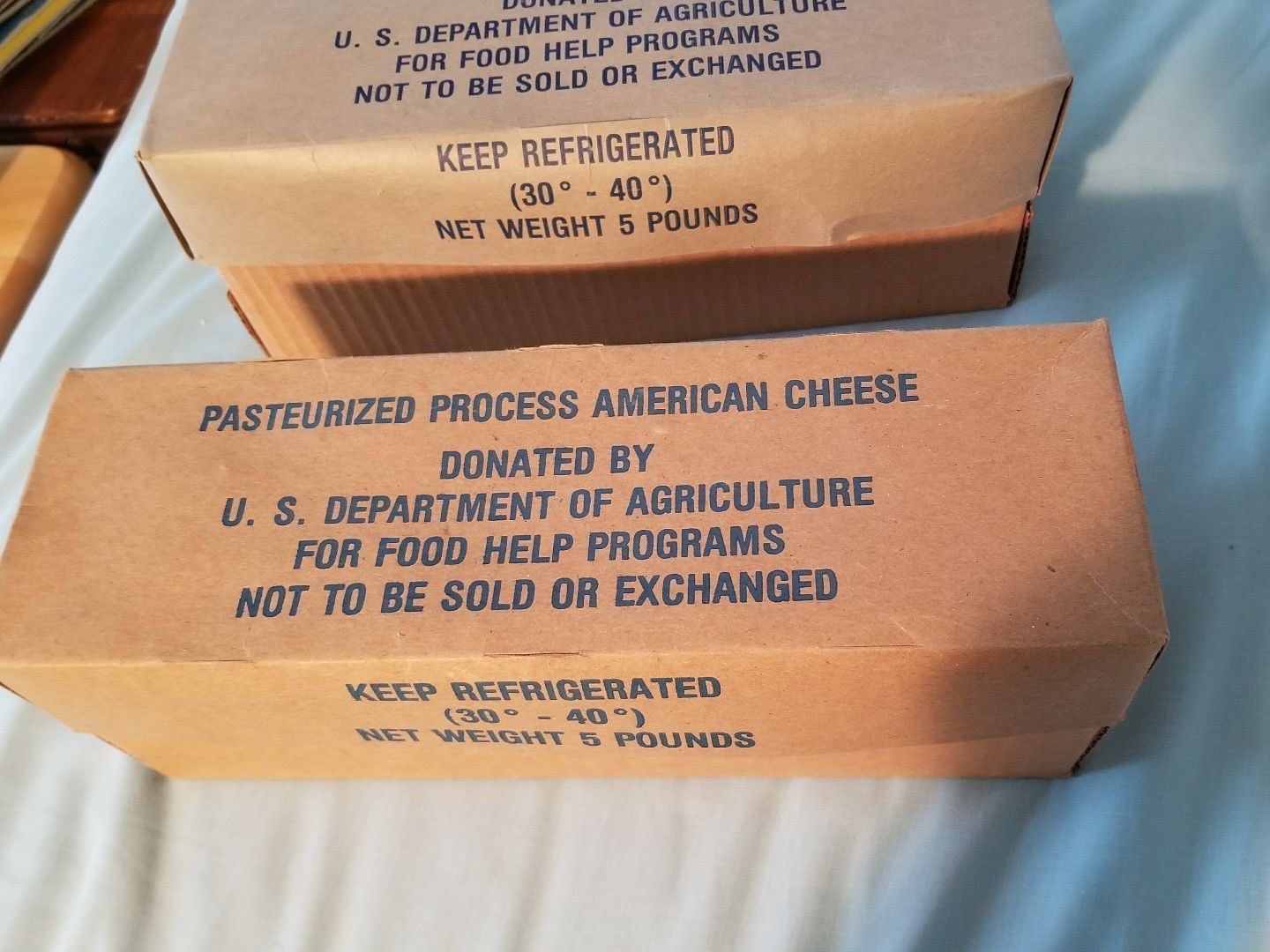

In a conversation that contained perturbed nostalgia, several of my classmates and I talked about bringing lunches to school due to the unaffordability of school lunch programs while standing at the exhibit about the actual costs and general lack of nutrition brought on by government requirements. After that, I fully took on the role of a visitor and looked through the exhibits for my most valued memory of government-provided food called by the simple moniker “government cheese.” But for all the appropriately elaborated-upon food chain problems and government distribution failures in the exhibition, the one thing that, at least in my opinion, the social programs got right was oddly not to be found. I walked through more than once looking for that relic of the Regan administration’s sustenance programs. But the iconic USDA stamped waxy brown cardboard box was missing from the displayed historical canon. I asked those present who were old enough if they remembered it, only to find out that I came from a background with a history of more food insecurity than the majority of them. Only two people knew about what I was referring to. One person had been given it at camp, and another, like my family, received it as food supplementation. What I have always perceived as a commonality for some generations is perhaps not as common as I thought. Should I ever find myself curating an exhibition on hunger issues in America, the politically controversial and socially divisive object that is “government cheese” will be represented.